Egon Schiele

Tulln 1890–1918 Vienna

1890–1905

Egon Leo Adolf Schiele was born on 12th June 1890 in Tulln. His mother, Maria “Marie” Schiele (née Soukup, 1862–1935), hailed from the southern Bohemian town of Český Krumlov and was the daughter of a building contractor. His father, Adolf Eugen Schiele (1850–1904), had roots in northern Germany; working as station master of Tulln railway station, he lived with his family (Fig. 1) in a company apartment on the first floor of the station building. The couple also had three daughters: The first-born daughter Elvira (1883–1893) died at the age of only ten; Melanie (1886–1974) was born four years before Egon, and Gertrude (1894–1981) four years after her brother. The younger sister “Gerti” modeled for Egon from an early age, and was the sibling he was closest to.

Between 1896 and 1900, Egon Schiele attended primary school in Tulln. He was already an avid draftsman, repeatedly drawing trains and other motifs from Tulln railway station. In 1901, he was sent to high school in Krems, but, due to ill success, was transferred in 1902 to a newly opened secondary school in Klosterneuburg, where he stayed with his former tutor, among others. Schiele’s academic performance remained poor.

From 1902, the health of Schiele’s father deteriorated rapidly – it is believed today that he suffered from syphilis. In the autumn of 1904, he became unable to work, and the family moved to Klosterneuburg. Adolf Schiele died on New Year’s Eve of that year. His death was a great loss to his son.

Egon Schiele’s wealthy and conservative uncle Leopold Czihaczek (1842–1929), who lived in Vienna and worked as an engineer and chief inspector for the Imperial-Royal State Railway, assumed guardianship of Egon. From this time onwards, Egon and his sister Gerti made frequent use of the free ticket issued by the State Railway to semi-orphans. They visited Trieste several times, where their parents had spent their honeymoon.

1 | Josef Müller: Marie and Adolf Schiele with their children Egon, Melanie and Elvira, 1893

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1906–1908

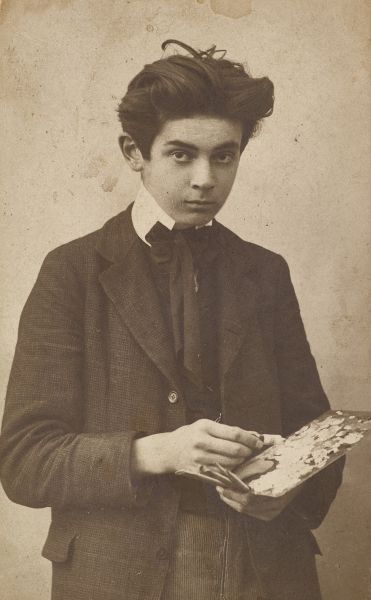

Czihaczek had intended for Schiele to study at the Technical University in Vienna, but his grades upon leaving school had been too poor. Several of his teachers encouraged him to seek artistic training – an idea that also found favor with his mother. In the autumn of 1906, Schiele successfully applied to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, and became the youngest student of his year (Fig. 2). Marie Schiele subsequently moved with her children to Vienna. Among his fellow students, Egon Schiele soon found like-minded people, including his future brother-in-law Anton Peschka (1885–1940). The curriculum’s emphasis was on drawing on paper.

In 1907, Schiele first sought contact with Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), the celebrated master of Viennese Jugendstil. Schiele derived vital artistic impulses from Klimt, who also introduced the young artist to other artists and collectors. Schiele’s first studio was located at Kurzbauergasse 6 in Vienna’s 2nd district. From 1907, the colors and shapes propagated by Jugendstil entered into Schiele’s palette, and his works increasingly boasted a square format: Klimt’s influence had become unmistakable.

In May 1908, Schiele participated in his first exhibition in Klosterneuburg. It was there that Heinrich Benesch (1862–1947), superintendent of the Austrian Southern Railway, became aware of the young artist. Though he was not a wealthy man, Benesch would become one of the most important collectors of Schiele’s works on paper over the years – today, his collection forms the core of the Schiele holdings at the Albertina in Vienna.

2 | Adolf Bernhard: Egon Schiele with Palette, September 19063

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1909

In 1908/09, Schiele advanced to the general painting class of Christian Griepenkerl (1839–1916), one of the leading exponents of Vienna Ringstraße painting. His relationship with the reactionary professor was difficult from the beginning, and Schiele earned barely passing grades in almost all subjects.

At the invitation of Gustav Klimt, Schiele received the opportunity in the summer of 1909 to participate in the Internationale Kunstschau [International Art Exhibition] in Vienna. There, he was introduced to the architects and designers Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956) and Eduard Wimmer-Wisgrill (1882–1961), as well as to other representatives of the Wiener Werkstätte.

In the wake of severe disputes with Griepenkerl – who was confronted with suggestive questions in a petition – several students left the Academy. Shortly before, Schiele had founded the artists’ association Neukunstgruppe together with fellow students, with Schiele acting as both the association’s president and secretary. The first exhibition held by the collective took place in December 1909 at the Kunstsalon Pisko on Schwarzenbergplatz, Vienna. Anton Faistauer (1887–1930) designed the exhibition poster (Fig. 3), while Schiele wrote a manifesto, which was printed with slight alterations five years later in the Berlin periodical Die Aktion: “There are only few, very few New Artists [Neukünstler]. Chosen ones. The New Artist must absolutely be himself; he must be a creator; he needs to have the basis on which to build inside him, immediately and by himself, without using all that has been handed down from the past.”

3 | Anton Faistauer, Poster for the first exhibition of the Neukunstgruppe at the art salon Pisko in Vienna, 1909, Private collection

Photo © Leopold Museum, Vienna

Photo © Leopold Museum, Vienna

1910

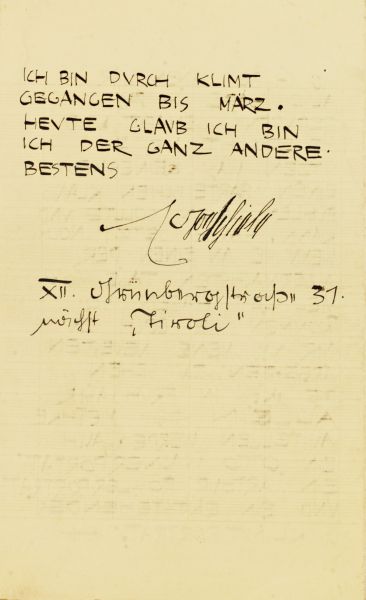

In 1910, Schiele arrived at his own, unique expressive art. Breaking with the Academy also meant breaking with the esthetic-decorative conventions of Jugendstil. In a series of swiftly created watercolors and paintings, he embarked on a path towards the most radical Expressionism. In November 1910, Schiele wrote in a letter (Fig. 4) to the art historian Josef Strzygowski (1862–1941): “I went through Klimt until March. Today, I believe I am quite different.”

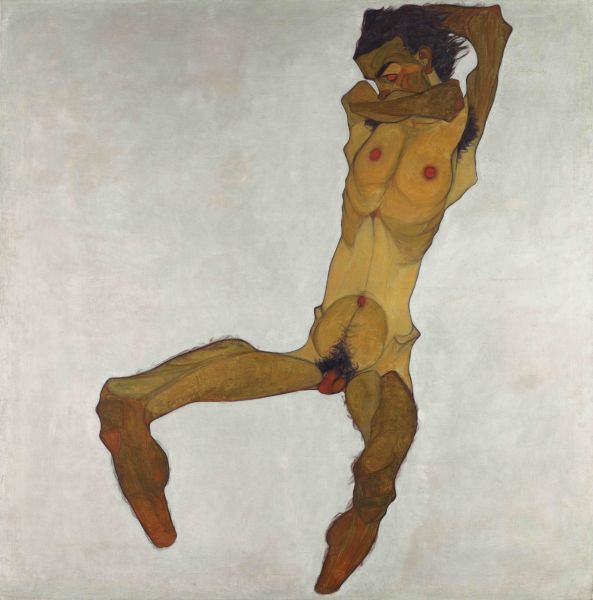

The design patterns of Jugendstil, based on ornaments and planar elements, moved into the background almost abruptly. Instead, Schiele now made the human body and bodily gestures the main subject of his works (Fig. 5). In his tense yet fragile figures, he combined beguiling beauty and tragic ugliness, as well as sharp-edged lines and denaturized colors, in a psychological quest for truth behind the veneer.

At the time, he started to write poems inspired by Arthur Rimbaud (1854–1891). Poetic titles now also accompanied his paintings. Arthur Roessler (1877–1955) came into the artist’s life as a critic, and subsequently became an important mentor, who introduced him to the collectors Carl Reininghaus (1857–1929) and Oskar Reichel (1869–1943).

His friend Erwin Osen’s (1891–1970) eccentric character made a lasting impression on Schiele. Osen shared a studio with Schiele on Alserbachstraße and posed for a series of watercolors; from May 1910, the two, together with Peschka, spent several months in Krumau – against the will of Schiele’s guardian Czihaczek.

His friend Erwin Osen’s (1891–1970) eccentric character made a lasting impression on Schiele. Osen shared a studio with Schiele on Alserbachstraße and posed for a series of watercolors; from May 1910, the two, together with Peschka, spent several months in Krumau – against the will of Schiele’s guardian Czihaczek.

4 | Letter from Egon Schiele to Josef Strzygowski, November 1910

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

Osen’s partner, the dancer Moa Mandu, was also captured by Schiele in various drawings. His encounter with the artist Max “Mopp” Oppenheimer (1885–1954) turned into a long-lasting friendship, with the two artists posing for one another and working together for months at a time.

At Vienna’s 2nd Women’s Clinic, Schiele drew newborns and pregnant women, likely with the support of the gynecologist Erwin von Graff (1878–1952) who was working there. These depictions were yet another formulation of the existential themes of sexuality, fertility, birth, frailty and death that had captured the artist’s imagination.

Schiele’s contributions to various exhibitions received positive feedback. In February 1910, the second exhibition of the Neukunstgruppe was held at the Klub Deutscher Künstlerinnen [Club of German Women Artists] in Prague. Along with Schiele, the presentation now also featured works by Faistauer, Hans Böhler (1884–1961), Albert Paris Gütersloh (1887–1973) and Rudolf Kalvach (1883–1932). The group made far-reaching plans at the point of intersection between painting and literature.

At the invitation of Josef Hoffmann, the head of the Wiener Werkstätte, Schiele participated in the Erste Internationale Jagdausstellung [First International Hunting Exhibition], held at the rotunda of the Vienna Prater from May to October 1910. He showed a now lost painting of a life-sized seated female nude. When Emperor Franz Joseph saw the work, he is said to have turned away, exclaiming: “But this is awful!”

5 | Egon Schiele, Seated Male Nude (Self-Portrait), 1910

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1911

The artist Albert Paris Gütersloh wrote an impressive essay on Schiele. The first collective exhibition was held at Galerie Miethke, where Schiele met the Munich art dealer Hans Goltz (1873– 1927), through whom he was able to participate in several presentations in Germany throughout the following years. In November, Schiele – likely on the initiative of Oppenheimer – was accepted as a member of the artists’ association Sema, whose other members included Paul Klee (1879–1940) and Alfred Kubin (1877–1959).

In the spring, he met and fell in love with his model Walburga “Wally” Neuzil (1894–1917) (Fig. 6). Together, they moved to Krumau, where Schiele embarked on one of his most fruitful artistic periods. But his concubinage with Neuzil, and his habit of drawing nudes outdoors caused offence, and the couple were forced to leave Krumau in early summer.

Soon afterwards, Schiele settled in Neulengbach, a small rural community close to Vienna. He enjoyed the countryside and intended to stay there indefinitely. Throughout the ensuing months, the artist created important paintings, which he would present in various exhibitions in Austria and Germany the following year.

6 | Anonymous: Wally Neuzil, 1913

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1912

In January, Schiele exhibited together with Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951), Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) and other artists at the Művészház in Budapest. Further presentations of his works followed in the spring exhibitions of the Vienna Hagenbund and the Munich Secession.

This time of early creative success came to an abrupt end: After charges brought by Ritter Theobald von Mossig in April 1912, Schiele was investigated on suspicion of abduction and rape of 13-year-old Tatjana von Mossig, as well as for offending morality by allowing minors access to his depictions of nude girls. Schiele was detained on 13th April 1912 at Neulengbach prison, where he was remanded in custody for 21 days. During the trial in St. Pölten, he was acquitted of the charges of abduction and sexual abuse, but was sentenced to three days imprisonment for “gross violation of morality and modesty causing public nuisance”, as he had hung up erotic drawings in a room frequented by minors. The affair plunged Schiele into a severe personal crisis.

Following this incident, known as the “Neulengbach Affair”, Schiele returned to Vienna, and briefly took over Osen’s studio at Höfergasse 18, while the latter was spending the summer in Krumau. That summer, Schiele embarked on several trips and visited some of his favorite places from the past, including Trieste, where he created studies of boats in the harbor. In August, he traveled to Munich, where he saw works by the German Expressionists. Wally Neuzil accompanied the artist to the Wörthersee in Carinthia and to Lake Constance in Vorarlberg.

The international exhibition of the artists’ association Sonderbund held in Cologne from May to September – one of the most eminent presentations of the pre-war era featuring more than 600 exhibits and affording an overview of contemporary art – included three paintings by Schiele.

In the summer, Schiele entered into an animated exchange with the German patron of the arts Karl Ernst Osthaus, a museum founder and head of the artists’ association Sonderbund. Osthaus organized an exhibition at the Folkwang Museum in Hagen, showing works by Schiele and Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919) side by side. Osthaus purchased the painting Dead City (VI) for the museum’s collection. This was the first acquisition of a Schiele work by a museum.

In the summer, Schiele entered into an animated exchange with the German patron of the arts Karl Ernst Osthaus, a museum founder and head of the artists’ association Sonderbund. Osthaus organized an exhibition at the Folkwang Museum in Hagen, showing works by Schiele and Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919) side by side. Osthaus purchased the painting Dead City (VI) for the museum’s collection. This was the first acquisition of a Schiele work by a museum.

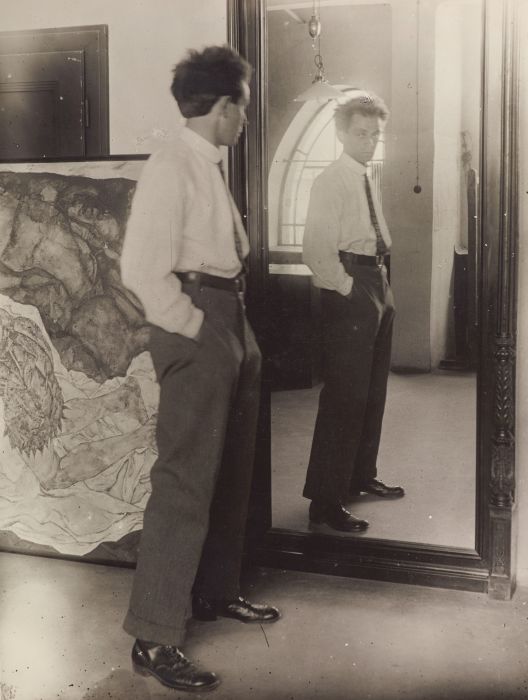

In October, the artist found a suitable studio at Hietzinger Hauptstraße 101 in Vienna’s 13th district, which he would use until the end of his life (Fig. 7). Schiele had the walls painted white, while he kept all the furniture in various shades of black.

During this time, Neuzil was his most important but never his only model. Rather than posing for free, she received payment for the sittings like all of his other professional models. She supported the artist in his everyday business affairs. Schiele made no secret of his relationship with Neuzil, neither with his patrons and collectors nor his family.

Klimt introduced Schiele to the industrialist and eminent art collector August Lederer (1857–1936). Together with his wife Serena Lederer (1867–1943), he was among the most important collectors of Klimt’s works. Their son Erich (1896–1985) became Schiele’s pupil and friend. Schiele spent Christmas and New Year’s with the Lederer family at their estate in the Hungarian town of Győr.

7 | Johannes Fischer: Egon Schiele in front of the mirror in his Hietzing studio, 1915

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1913

Schiele won increasing renown as an artist. On 17th January 1913, he was admitted into the Association of Austrian Artists presided over by Klimt. This was followed by exhibition participations in Budapest, Munich, Düsseldorf, Dresden and Berlin. From June to July, the Munich Galerie Goltz dedicated a large solo exhibition to Schiele. In Vienna, he participated in the Internationale Schwarz-Weiß-Ausstellung [International Black-and-White Exhibition] and the 43rd Exhibition of the Vienna Secession. Some of his drawings and prose poems were published in the Berlin periodical Die Aktion.

Schiele traveled once more to Trieste, visited Salzburg and Munich, and holidayed for more than a month at Lake Ossiach in Carinthia. Together with Neuzil, he visited Maria Laach on Jauerling Mountain in the spring, where he made an artistic entry into the guest book. During the summer months, the couple spent a week in Krumau. In July, he was invited by Arthur Roessler and his wife Ida Roessler (1877–1961) to spend a few days at their residence in Altmünster on the Traunsee, and took Neuzil along for the trip (Fig. 8).

8 | Anonymous: Egon Schiele and Arthur Roessler in front of Schloss Ort, July 1913

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1914

The house opposite Schiele’s studio at Hietzinger Hauptstraße 114 was home to the bourgeois Harms family. At the beginning of the year, the artist started a dalliance with the two daughters Edith (1893–1918) and Adele (1890–1968). Via Goltz in Munich, Schiele received the offer of an extended stay in Paris – a trip he never actually made. Schiele considered moving to Berlin or Munich.

When the heir to the throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand was murdered in Sarajevo, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28th July. The general mobilization of troops began three days later. Schiele did not share many of his fellow artists’ patriotic enthusiasm for the War. Following two army medicals, Schiele was deemed unfit for military service, and was initially spared serving in the War.

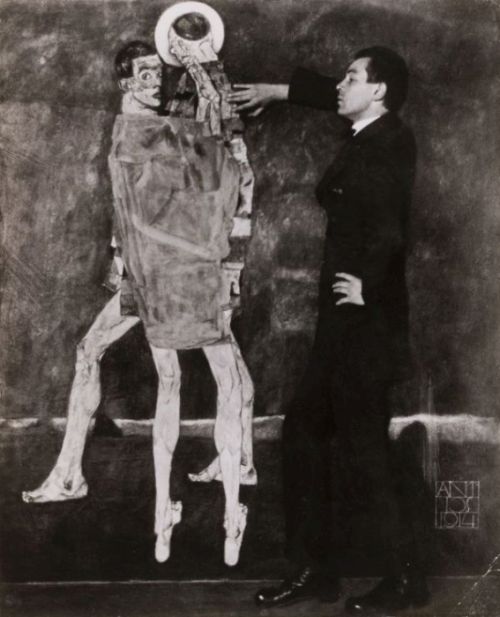

The artist started to experiment with new techniques, and was instructed by the painter and graphic artist Robert Philippi (1877–1959) in the printing technique of etchings. In cooperation with Anton Josef Trčka (1893–1940) and Johannes Fischer (1888–1955), he experimented with photographic self-portraits in expressive poses (Fig. 9).

Despite the outbreak of World War I, Schiele increasingly participated in exhibitions. That year, he exhibited his works for the first time outside of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy: in Rome, Brussels and Paris.

Despite the outbreak of World War I, Schiele increasingly participated in exhibitions. That year, he exhibited his works for the first time outside of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy: in Rome, Brussels and Paris.

9 | Anton Josef Trčka: Egon Schiele in front of his lost painting Encounter, 1914

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1915

In early 1915, Galerie Arnot in Vienna dedicated a one-month solo exhibition to the young artist, which featured 16 paintings and numerous works on paper.

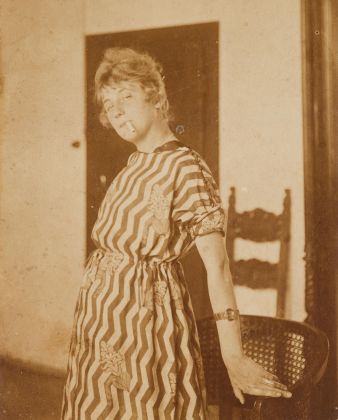

In the spring, Schiele and Wally Neuzil separated, after Edith Harms (Fig. 10) had demanded “a clean break”. Schiele and Harms were married on 17th June 1915 in Vienna, followed by a brief trip to Prague: Schiele had been drafted into the military in Prague, having been deemed fit for service after a third medical at the end of May. On 21st June, he started his service as a One-Year Volunteer in Prague; four days later, he began basic military training in Jindřichův Hradec, Bohemia, where Edith followed him.

Later he was stationed in Baumgarten, on the Exelberg near Vienna, and in Gänserndorf. He created a series of portraits of Russian prisoners of war. Schiele had little time for other artistic activities.

Later he was stationed in Baumgarten, on the Exelberg near Vienna, and in Gänserndorf. He created a series of portraits of Russian prisoners of war. Schiele had little time for other artistic activities.

10 | Anonymous: Edith Schiele with Striped Dress and Cigarette, c. 1915

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

1916–1917

In January 1916, Schiele was able to participate in the exhibition Wiener Kunstschau at the Berlin Secession. There, his painting Transfiguration was presented in the same room as Gustav Klimt’s Death and Life.

In a war diary, he documented his everyday life during his deployment in Liesing, and later in a camp for captured officers in the Lower Austrian town of Mühling (Fig. 11). There, he continued to portray the Russian prisoners, depicting them in a deeply personal and empathetic manner.

In January 1917, Schiele was detailed to Vienna, where his superiors supported his work as an artist. Schiele started to make plans for the time after the War: “We know that the time of impending political peace will bring about a great clash between our civilization’s materialistic tendencies and those remnants of noble culture that this mercantile age has still left us.” Schiele took action by founding an inter-disciplinary artists’ association, the Kunsthalle, and co-organized the war exhibition Kriegsausstellung, held at the Vienna Prater from May to October. His first portfolio of twelve reproductions was published by Richard Lányi (1884–1942) in May 1917.

In a war diary, he documented his everyday life during his deployment in Liesing, and later in a camp for captured officers in the Lower Austrian town of Mühling (Fig. 11). There, he continued to portray the Russian prisoners, depicting them in a deeply personal and empathetic manner.

In January 1917, Schiele was detailed to Vienna, where his superiors supported his work as an artist. Schiele started to make plans for the time after the War: “We know that the time of impending political peace will bring about a great clash between our civilization’s materialistic tendencies and those remnants of noble culture that this mercantile age has still left us.” Schiele took action by founding an inter-disciplinary artists’ association, the Kunsthalle, and co-organized the war exhibition Kriegsausstellung, held at the Vienna Prater from May to October. His first portfolio of twelve reproductions was published by Richard Lányi (1884–1942) in May 1917.

11 | Anonymous: Egon Schiele with military colleagues and officiers, 1916

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

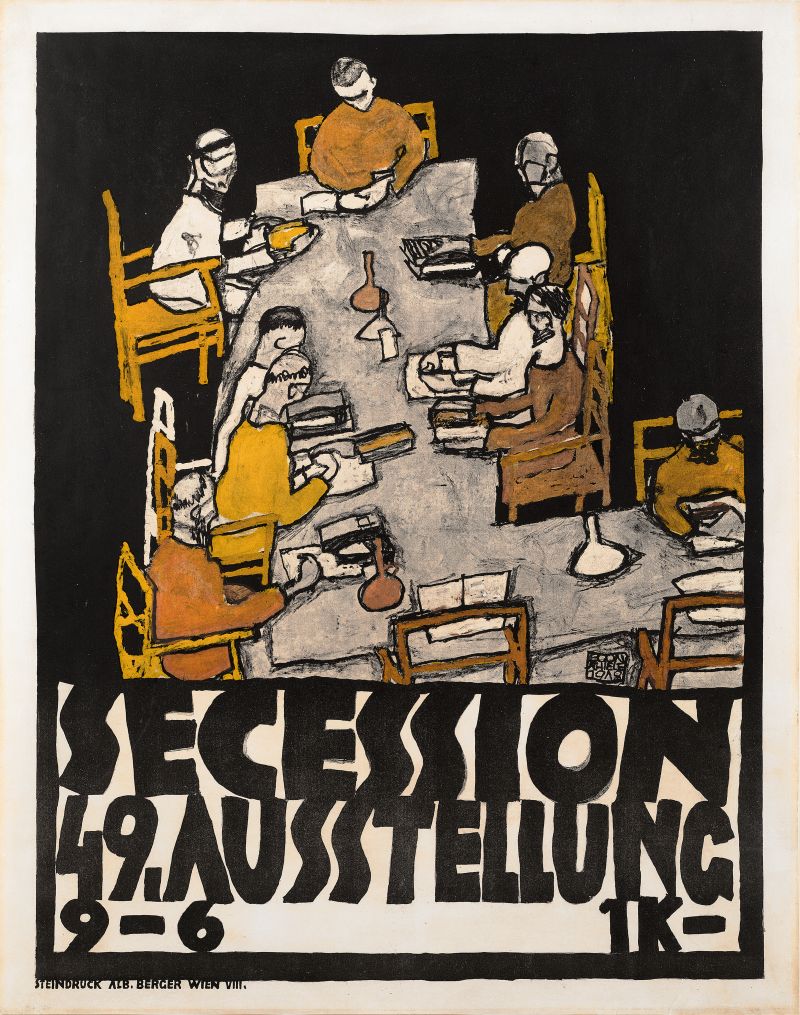

1918

The year 1918 marked Schiele’s greatest breakthrough: The 49th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession in March 1918 represented a highlight in his exhibition activities as well as an unprecedented financial success, with the artist presenting 19 oil paintings and around 30 drawings in the central exhibition hall. He sold five paintings and several drawings. The Österreichische Staatsgalerie (later: Belvedere), under its then director Franz Martin Haberditzl (1882–1944), acquired the painting Portrait of the Aritst’s Wife, Edith Schiele – the first acquisition of a Schiele painting by an Austrian museum. His poster for the exhibition Round Table, became a manifesto of artist friendship (Fig. 12). Schiele can be seen presiding over the table, while the place opposite him is said to have been intended for Gustav Klimt in the draft, before the latter died on 6th February following a stroke. In the magazine Der Anbruch, Schiele published an obituary: “GUSTAV KLIMT | An unbelievably accomplished artist | A man of rare depth | His work a sanctuary.”

Schiele subsequently founded the artists’ association Neue Secession Wien, and planned presentations in Prague, Munich, Budapest and Zurich, some of which were realized. In the summer of 1918, he rented a large additional studio at Wattmanngasse 6, and planned to hold a “drawing and painting school” as well as a “master class for painting” at his previous studio on Hietzinger Hauptstraße. Following disputes within the Neue Secession Wien, he founded the Sonderbund in September.

In late October, Edith, who was six months pregnant, contracted the Spanish Flu, while Egon Schiele fell ill a few days later. Three days after Edith’s death, Egon Schiele died on 31st October 1918. His last words, recorded by Adele Harms, would come true: “The War is over – and I must go. My paintings shall be shown in all the world’s museums.”

In late October, Edith, who was six months pregnant, contracted the Spanish Flu, while Egon Schiele fell ill a few days later. Three days after Edith’s death, Egon Schiele died on 31st October 1918. His last words, recorded by Adele Harms, would come true: “The War is over – and I must go. My paintings shall be shown in all the world’s museums.”

12 | Egon Schiele, Round Table. Poster for the 49th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession, 1918

© Leopold Museum, Vienna

© Leopold Museum, Vienna